Do you think the follow statements are true or false?

1. "Politics has become unreal"

2. "The Pope endorses Trump"

3. "The Clintons bought a $200 million house in the Maldives"

4. 60% of US adults for example get their news from social media

5. "Facebook is able to influence political voting and political behaviour by adjusting its sites."

6. "Social media tends to confirm, rather than challenge, your political views."

7. "Donald Trump won the popular vote as well as the electoral vote"

Listen to the end of the first transcript:

Intro questions:

1. What is the distinction between fabricated and biased news?

2. what percentage of people in the U.S get their news through social media?

3. What's a filter bubble?

Listen to the end of the first transcript:

soundbites and snippets

propaganda

misinformation.

chucked a u-ey

the lead

scrolled through

endorses

made-up news

heavily biased

outright fake news

fabricated, not just spun

converse

quantify

political discourse,

biases

algorithm

newsfeeds

highly partisan

the filter bubble

right-leaning

bumped up

track down

reportedly

lobby for change

trolling and abuse

revenues

filter it out of feeds

disrupting

not factually

correct.

highlighted

indication

play this down

viciousness

Tactic

Part 2:

political turmoil

progeny

the field

at first

digital petition

an earlier era

transaction costs

lumpy

bemoaning

crisis

drawing people into politics

prejudices

symbols

sphere of acquaintances

wider sphere

scale up

political mobilisation

kicked off

organisational trappings

waiting in the wings

mainstream politics

mechanisms

creaking at every conceivable seam

to accommodate

symmetry

Jihadists

right-wing

distinctive characteristics

analogous

intimacy

facility

benign ends

closing off

antidotes

counteract

deliberation

chaotic pluralism

bite-size chunks

transparency

gatekeepers

Transcript:

Robyn Williams: Politics has become unreal, as both President Obama and Mark Zuckerberg admitted this week.

Barack Obama: Particularly in an age of social media were so many people are getting their information in soundbites and snippets off their phones, if we can't discriminate between serious arguments and propaganda, then we have problems.

Mark Zuckerberg: We can work to give people a voice, but we also need to do our part to stop the spread of hate and violence and misinformation.

Robyn Williams: And now Mark Zuckerberg has chucked a u-ey and will take measures to try to clean up Facebook. How bad is it? This is how Patricia Karvelas presented the problem on Drive on RN a few days ago.

Patricia Karvelas: In the lead-up to the US presidential election you might have seen these headlines as you scrolled through Facebook. The Pope endorses Trump. Hillary Clinton bought $137 million in illegal arms. The Clintons bought a $200 million house in the Maldives. These were just some of the fake news stories posted online and shared by millions. After the election of Donald Trump, websites like Facebook and Google are being forced to reflect on the role they played in making completely made-up news widely available.

Dr David Glance is the director of the University of Western Australia's Centre for Software Practice. First of all, let's get straight to what we're talking about here. There's news that is heavily biased but we are talking about outright fake news, right, completely fabricated, not just spun.

David Glance: Yes, it's completely made up and it is designed specifically to appeal to a specific audience. So in the election it really was designed to either satisfy Trump supporters or the converse with Hillary supporters.

Patricia Karvelas: Is there any way to quantify what impacts this is having on our political discussion, our political discourse, the way that people are making their minds up?

David Glance: Well, we know from other evidence that 60% of US adults for example get their news from social media. We also know from experiments that Facebook themselves have run in the past that they are able to influence political voting and political behaviour by adjusting their sites. So they themselves have admitted to the ability to actually get more people to vote, for example, and register to vote. So yes, we do know that it does have an influence. And if you look at some of these fake stories they are shared hundreds of thousands of times, so they are certainly confirming the biases and also the views of the supporters in these types of elections, especially this one.

Patricia Karvelas: Does the algorithm that controls what people see in their Facebook newsfeeds reward highly partisan untrue stories?

David Glance: Yes, absolutely. So this is all part of the process that is called the filter bubble which really tends to favour things that you yourself want to see. So based on your preferences. So if you are right-leaning then you will see that type of news, and fake news really appeals to that and gets bumped up in terms of the algorithm. But also it's the types of people that are sharing it, and the groups that are sharing it, so it's not just a question of one site, for example, publishing a story and that single site then being shared, it's then reprinted and republished on dozens of different sites. So it's very difficult to actually manage, track down or stop.

Patricia Karvelas: A group of Facebook workers, employees, is reportedly concerned about this. They've formed a group to lobby for change from within the company. What changes do you think they'll be asking for and do they have any chance of actually achieving it?

David Glance: Well, it's going to be difficult, and certainly the same problem has been the case on Twitter with not dealing with the general trolling and abuse problem that they've had. So on the one hand this fake news is motivated by driving revenues for advertising, and of course Facebook and Google are benefiting from this. But it's also a difficult problem to crack down on because it's actually how do you identify fake news in the first place is one problem. And then secondly how do you then filter it out of feeds without actually penalising the fact that somebody wants to share something and say, hey look what I found, some fake news. So without disrupting the whole of the newsfeed, it's exactly quite difficult to deal with this problem, and think that's why Facebook hasn't really dealt with it up until now.

Patricia Karvelas: What about Google, if you googled 'final election results', the top story under News was a fake news story on a fake news site with incorrect information about Donald Trump winning the popular vote as well as the electoral vote, and I actually heard this in a US podcast, they were talking about how people started believing yesterday as a result of this story, which is pretty incredible because it's not factually correct. What can Google do to weed out fake news?

David Glance: Well, that was quite remarkable because it's still there, and it's based from a site which is a blog, which isn't really advertising, and there's no real reason why that story should have been highlighted above others, and I think this is just an indication of when you depend on computer software to decide what's important or not. Sometimes it just gets it wrong, and in this case, you're absolutely right, it has the potential to influence the behaviour of all the people who are currently demonstrating, for example, and using the basis that Clinton is leading in the popular vote as the basis for demonstrating. So it's really not clear why this story should have got to the top, but certainly Google's algorithms are to blame for that.

Patricia Karvelas: A Facebook spokesperson has said this week, again a quote, 'While Facebook played a part in this election, it was just one of many ways people receive their information.' I wonder if that's true, and I say that as somebody who knows lots of people around me who are pretty much consuming a lot of their stories via Facebook. They have incredible power.

David Glance: Absolutely. And Trump himself, provided we can believe it of course declared that he won the election in large part because of his influence on Twitter, Facebook and other social media. And we do know there is plenty of evidence Zuckerberg is really trying to play this down because they don't want to be held responsible for an outcome that he didn't agree with, and also the majority of his employees probably don't agree with either. But yes, it has an enormous impact and I think we saw that even from Obama's election that social media really plays a key part in this. Fake news really came to the fore in this election because of the general viciousness of the campaigns, and so I think that this is a tactic that we will see more of. So it's not just people profiting from the advertising, it's also the fact that people can actually just do this to affect political views with great success.

Robyn Williams: Dr David Glance from the University of Western Australia, director of the Centre for Software Practice, with Patricia Karvelas on RN Drive.

Discuss

1. What is the "filter bubble"?

2. Do you share "news" via social media?

3. Have you ever received or even posted "fake news"?

4. How do you make sure the news and information you're consuming and sharing is authentic?

Part 2:

Agree or disagree?

- The internet is having positive effect on politics over all.

Are the following things positive or negative influences according to Helen and Robin?

1. having a disruptive effect

2. you can do a little bit of politics as you go about your daily life

3. you kind of confirm your prejudices without leaving the room

4. young people's experience has expanded to a much wider sphere

5. Social and political movements can scale up really dramatically, but almost always they fail

6. we used to identify something we cared about, identify other people who cared about it too, form some sort of collective identity and then mobilise around that. Now you're seeing people acting and identifying later, or perhaps not at all

7. mainstream parties can't cope with the new form of political mobilisation and are falling apart

8. ISIS has used social media very successfully

9. you can say something fairly brief and powerful and have an effect, whereas if you want to talk about democracy, it's kind of complicated

10. I don't think the internet is very good for deliberation really. I think it's like asking a toaster to make scrambled eggs.

11. I'm getting stuff which is 90% useless

12. you don't have any influence over the algorithms which decide what information you find when you search for something

Put these samples into the best gap

otherwise

to that view

there are ways in which

I would say that

it would seem that

1. has the internet and its progeny given us politics we would not ________ have?

2. at first sight _______ in most of our countries, let's say Australia and Britain, clearly America, democracy is in a state of chaos.

3. I think the internet is definitely having a disruptive effect, but I think ______ you can see that as positive.

4. So in that sense ________ social media in particular is drawing people into politics who didn't traditionally participate, and I'd see that as a democratically good thing and an exciting thing.

5. I don't subscribe ________ at all.

So the big question in these times of political turmoil is this; has the internet and its progeny given us politics we would not otherwise have? Has it changed the nature of democracy? This is very much the field of Professor Helen Margetts, director of the Internet Institute at Oxford.

What sort of effect, broadly, do you see the internet having on the democratic process? Because at first sight it would seem that in most of our countries, let's say Australia and Britain, clearly America, democracy is in a state of chaos. Would you blame the internet at all for some of that disruption?

Helen Margetts: Well, I think the internet is definitely having a disruptive effect, but I think there are ways in which you can see that as positive. The internet and particularly social media make very small acts of political participation possible, acts so small that they have very few costs associated with them, and I mean things like liking or sharing or following or viewing or downloading or signing a digital petition or something like that, these are tiny acts which in an earlier era wouldn't have been possible because the transaction costs would have been too great.

So it means that instead of if you want to be politically active having to do something quite lumpy, like join a political party or something like that, you can do a little bit of politics as you go about your daily life. And that's quite exciting. It's drawing a lot of people into politics who perhaps just weren't there at all before, who weren't doing anything, any kind of political participation, particularly young people. For ages we've been bemoaning the kind of crisis that young people don't care about politics anymore, and I think we're finding that actually they do and they are willing to do something about it, as long as it is presented to them in their everyday lives, which it is. The average young person in this country, and I don't suppose it's very different in Australia, has an average of five active social media accounts. And although a lot of that is about chatting and socialising and dating and shopping and music and all those things which are perhaps more exciting than politics, there is politics in the mix too, and people are taking those opportunities. So in that sense I would say that social media in particular is drawing people into politics who didn't traditionally participate, and I'd see that as a democratically good thing and an exciting thing.

Robyn Williams: On the other hand, may I suggest that you're talking about the old days, and in the old days they left home, walked around the village, walked around the high street, met people, may have had prejudices but actually saw people in front of them instead of symbols. And there may be a tendency with the internet at the moment that you kind of confirm your prejudices without leaving the room.

Helen Margetts: I don't subscribe to that view at all. Young people still walk around the village or the town or wherever, it's just that their sphere of acquaintances, of friends, of what they know about, of what's going on, their experience has expanded to a much wider sphere. So they're likely still to have micro local knowledge but also global knowledge. And again, I'd see that as a positive thing.

Moving on to the perhaps less positive and what you were maybe getting at at the beginning, the point about these very small acts is that they can scale up to something really dramatic, and we've seen that again and again, we saw it in the Arab Spring, we've seen it in a huge wave of political mobilisation that has stretched right across the world ever since the Arab Spring, people campaigning and mobilising for change. And that can happen and often it's kicked off by social media, that's how people get to hear about it, and that's how it scales up to something so big.

The trouble is that sometimes it scales up really dramatically, but almost always it fails. So if you take petitions, for example, that's really taken off in recent times, this is a tiny act of participation that has become very popular, 99.99% of petitions go absolutely nowhere, they fail even to get 500 signatures. But a few of them succeed really dramatically, get millions of signatures, and have caused policy change in all sorts of countries. And we don't know that much about why some succeed and some don't, but when they do succeed they succeed incredibly quickly, they go straight up. If a petition hasn't got 3,000 signatures in the first 10 hours then it's almost certainly going to fail. And that makes them quite unpredictable. It also means because you can get a million people in a square or hundreds of thousands of people on the street, you can do that when it happens without any of the normal organisational trappings of a political movement.

The old way that we used to think about social movements for example was that people would identify something they cared about, they would identify other people who cared about it too, form some sort of collective identity and then mobilise around that. Now you're seeing people acting and identifying later, or perhaps not at all. So the action is coming first, and that means you can get something like the Egyptian revolution without any of the normal organisational trappings of a revolution, without any political parties or political leaders waiting in the wings. Because this large-scale mobilisation can get going without those traditional things. So it makes political movements of today very unstable.

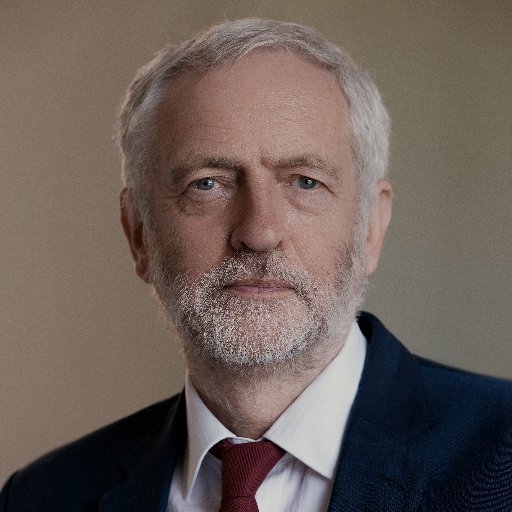

And we see that in mainstream politics too. In the UK you see Jeremy Corbyn, elected on a wave of social media enthusiasm by a lot of young people as leader of the Labour Party, but without any of the organisational mechanisms that you need to lead a major political party. In fact, almost the opposite of mechanisms that enabled him to lead. He had voted against the Labour Party so many times in parliament that people almost actively didn't want to vote for the things that he voted for. And now of course we have the Labour Party in complete crisis. A very traditional political institution utterly unable to cope with its new form of political mobilisation. You see the same in the US, you see the Republican Party utterly unable to cope with Donald Trump, creaking at every conceivable seam in an effort to accommodate what's going on, but in the end unable to do it and rushing towards destruction.

UK Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn

Robyn Williams: Well, perhaps Jeremy Corbyn can come out against himself and that will give some sort of symmetry to the activity. But one of the problems is that if you are a powerful group such as, shall we say, the Jihadists who are expert at using these new media for their own purposes and using strong propaganda finely focused and, as you implied, a certain group of right-wing people in the United States, you really can make a tremendously powerful hit, while most others, you and me, people listening, are simply getting on with their lives, they don't have the time or the power to focus that big hit through the internet, to change people so much. Do you think that use of new age technology propaganda is having such a powerful effect as well?

Helen Margetts: Well, obviously one of the distinctive characteristics of ISIS is that they've used social media very successfully. They are using it in ways I suppose analogous to famous musicians or celebrities. They are using it to give an appearance of intimacy with lots of individual people. And social media and the internet do give that facility. But, I mean, whatever technology we develop there will always be people who will use that to form a line, as well as benign ends of course.

So in a sense you're right, yes, they are using it really, really successfully, but that is I guess what we would expect. The answer to that was not to start censoring it or closing it off, and actually most of the antidotes to what ISIS are doing online are online, as you might expect, and security and intelligence services all over the world are working on ways to counteract what ISIS are doing online.

Robyn Williams: Well, I use the term propaganda in the sense that you can say something fairly brief and powerful and have an effect, whereas if you want to talk about democracy, it's kind of complicated. There are arguments, there are discussions and so on, and I wonder how in your research you are seeing this first stage of the internet is going to mature into a different form, if it is going to mature in that way.

Helen Margetts: I don't think the internet is very good for deliberation really. I think it's like asking a toaster to make scrambled eggs. And the internet is good for other things with democratic purposes and ends, but not that, and that's why in the book what we discuss is this idea of chaotic pluralism where there are multiple competing interests, groups, clusters of individuals, yes, putting forward more simple messages or undertaking, as I said, small acts, bite-size chunks of deliberation but not actually deliberation.

Robyn Williams: Going back to the personal, which I find terribly convenient and also terribly frustrating…the convenience of course is I can send you a message and make arrangements very, very quickly. On the other hand I've been sorting emails since five in the morning, as usual, and I'm getting stuff which is 90% useless, I'm on the other side of the world and reading about various people back in my office in Sydney, cleaning out the fridge, and there are 40 messages from people agreeing with the fact that it's quite good to clean out the fridge. Is the internet getting out of control?

Helen Margetts: Well, I think the whole point of it was that it was never in control, and most of us wouldn't want it to be controlled. The point is that you do have a lot of control yourself, so you might want to look at your spam filters by the sound of it. If you're getting emails about people cleaning out the fridge there probably is a way for you to avoid doing that. So I think we have quite a lot of control. There are all sorts of ways in which our relationships with each other and with organisations are affected by the internet and being shaped by the internet and social media platforms for example is affecting the way we live.

And there is something…to go back to the beginning of the discussion, there is something undemocratic about that, if you like, because the way in which you find out information or establish a friendship network on a social media platform is shaped by a mega corporation like Facebook or Google, very, very little transparency about how that's done. The algorithms which decide what information you find when you search for something are closely held secrets, and therefore if they are not transparent, the possibility that you can somehow in any way influence how those things are developed and changed, it's not there, you don't have any influence over it.

Robyn Williams: They call it the domination of FANG, don't they: Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google.

Helen Margetts: Yes, that's right, there might be a few that were left out there, and actually that's another thing, because children and grandchildren, they are using other things, and we know even less about those. My son is using WhatsApp all the time, for example, which was bought by Facebook, also Instagram. And on what other planet would a company be able to buy another company like that? This concentration in the internet giants is something which seems completely uncontrollable, and that is a worrying phenomenon. They are the gatekeepers to our political lives, our economic lives and our social lives. And we ought to be trying to institutionalise ways of knowing more about what they do and being able to make better choices.

Robyn Williams: Helen Margetts is professor of society and the internet at Oxford where she directs the Internet Institute, and her latest book is Political Turbulence: How Social Media Shape Collective Action.

The Science Show on RN.

| | | | | | | | | E1 | | | P2 | | | | | | | |

| | | | | M3 | I | S | I | N | F | O | R | M | A | T | I | O | N | |

| | L4 | | | | | | | A | | | E | | | | | | | |

| | O | | | | | | | B | | | J | | | | | | | |

| | B | | | | | | | L | | | U | | | | | T5 | | |

| | B | | | D6 | | | | E | | | D | | | | | R | | |

| S7 | Y | M | M | E | T | R | Y | | | | I | | | | | A | | |

| | | | | L | | | | E8 | | | C | | | A9 | | N | | |

| W10 | A11 | I | T | I | N | G | I | N | T | H | E | W | I | N | G | S | | |

| | C | | | B | | | | D | | | | | | A | | P | | |

| | C | | | E | | C12 | O | S | T | S | | | | L | | A | | |

| | O | | | R | | | | | | | | | | O | | R | | |

| | M | | | A | | E13 | | | | | | | | G | | E | | |

| | M | | | T14 | U | R | M | O | I | L | | | | Y | | N | | |

| | O | | | I | | A | | | | | C15 | | | | | C | | |

| | D | | | O | | | R16 | E | P | O | R | T | E | D | L | Y | | |

| | A | | | N | | | | | | | I | | | | | | | |

| | T | | | | | | | | | | S | | | | | | | |

| | E | | | | | A17 | C | Q | U | A | I | N | T | A | N | C | E | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | S | | | | | | | |

Across

3. false rumour, deceptive claims (14)

7. balance (8)

10. Off stage and ready to perform (7,2,3,5)

12. expenses, overheads (5)

14. chaos (7)

16. apparently, by all accounts, so the story goes (10)

17. a person one knows slightly, but who is not a close friend (12)

Down

1. make possible (6)

2. preconceived opinion (9)

4. seek to influence (a legislator) on an issue (5)

5. antonyms: opacity, cloudiness, obscurity, ambiguity, cunning, secrecy (12)

6. long and careful consideration or discussion (12)

8. purposes, goals (4)

9. parallel, resemblance (8)

11. fit in with the wishes or needs of (11)

13. epoch, period (3)

15. a time of intense difficulty or danger (6)