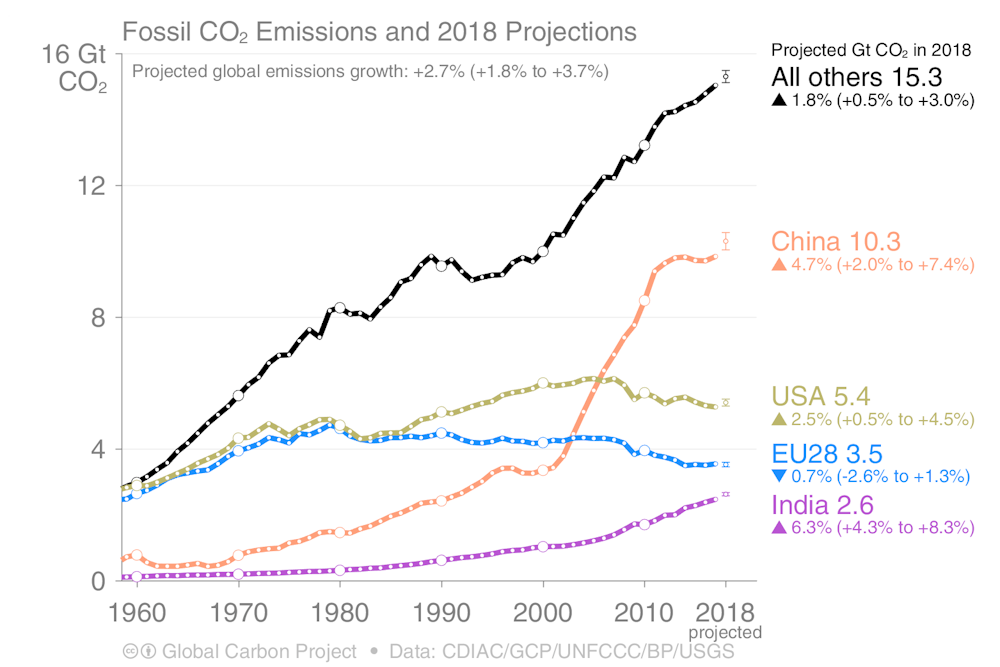

Discuss the graph. Why are C02 emissions going up?

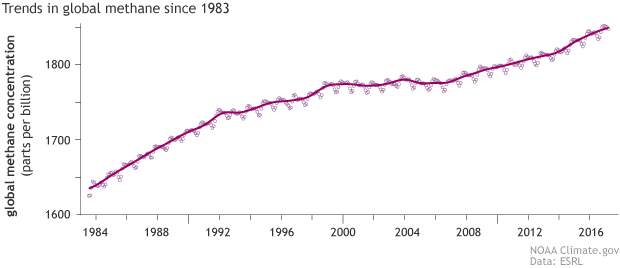

Why are methane emissions going up?

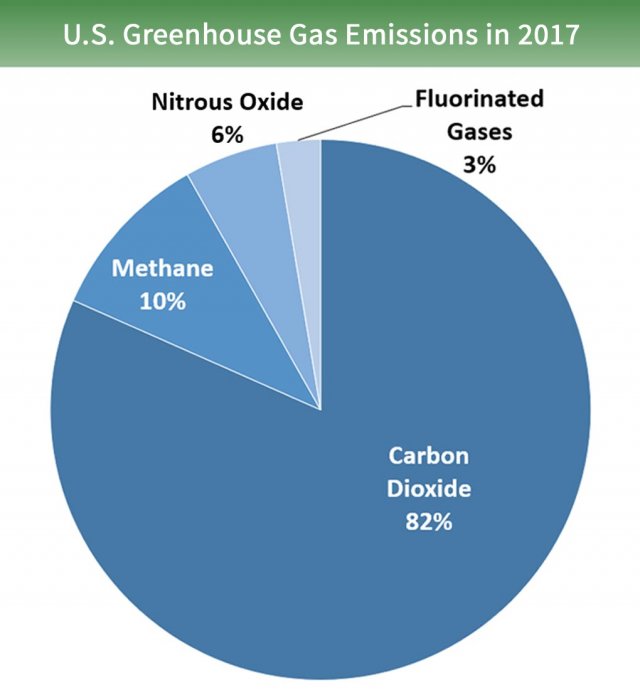

Why worry about methane emissions when they're only %10 of the total emissions?

Part 1: Comprehension and vocabulary

Link:

George Monbiot: Ending Meat & Dairy Consumption Is Needed to Prevent Worst Impacts of Climate Change

2:08 - 3:38

George Monbiot is calling for a new revolution with a global shift to a plant-based diet. The British author and journalist is a columnist with The Guardian. His latest piece for The Guardian is headlined "The Earth Is In a Death Spiral - it will wake radical action to save us". He has written extensively on the link between animal farming and climate change, has himself switched to a plant-based diet."

What do these words mean - give a definition in your own words

existential

biodiversity

habitat

crisis

atmosphere

revegetate

Watch / listen and answer these questions

1. George prefers the term climate breakdown / climate change.

2. Why does he prefer this term?

A) Because it is more dramatic

B) Because it is more honest

C) Because it is more unexpected

B) Because it is more honest

C) Because it is more unexpected

3. What does George mean by an "existential" crisis?

A) It threatens our existence

B) It is too late to prevent it

C) It is caused by human activity

B) It is too late to prevent it

C) It is caused by human activity

3. Removing _________ would free up land for revegetation.

A) carbon from the atmosphere

B) the destruction of soil

C) livestock

B) the destruction of soil

C) livestock

4. Which idea did George put the most emphasis on?

A) freeing up land for revegetation

B) stopping emissions

C) no longer using the term "climate change"

B) stopping emissions

C) no longer using the term "climate change"

Discuss

1. What do you think of George's argument so far?

2. What do you think farmers would say to George?

3:38 - 4:28

1. What do you think of George's argument so far?

2. What do you think farmers would say to George?

3:38 - 4:28

Before listening

True or false?

1. 70% of our agricultural land is not used to grow food not for humans but for farm animals.

2. 40% of our diet is produced by farm animals.

3. Feeding livestock by grazing them is more sustainable than feeding them on grain.

4. Grazing livestock don't need very much land.

Listen and check

Listen again for the figures

1. Amount of agricultural land livestock uses globally: %____

2. Percentage of our diet from livestock: %____

3. "a huge dirtionspropo" (unscramble)

1. Amount of agricultural land livestock uses globally: %____

2. Percentage of our diet from livestock: %____

3. "a huge dirtionspropo" (unscramble)

4. "it's a fantastically astwuefl way of using land."

4:55-

2. To graze cattle you have to...

kill _________

exclude _________

wipe out _________,

cause a radical fiiosicatmplin of the ecology.

3.Which negative effects of livestock farming does George mention:

destruction of coral reefs, polluting of water supply, bush fires, soil erosion, air pollution, low carbon holding capacity, flooding

4. "If you want to eat less soya, you should eat soya" - why does George say this?

Skill: Linking and highlighting

Discuss

When you're trying to persuade someone to adopt your point of view, how do you make sure they get the points you're making and see how they add up?

George is a master of linking and highlighting his points. I have enlarged the language he uses to do this. It's not difficult language, but extremely useful and persuasive.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Can you explain, George, the amount of agricultural land that’s being used to produce food for the livestock—for the livestock and not for human beings—and why you think that’s especially injurious to the climate?

GEORGE MONBIOT: It’s quite remarkable, really. Livestock account for 83 percent of our agricultural land use, according to one study, and produce 18 percent of our diet. It is a huge disproportion. Now when you look specifically at grazing livestock, which people tend to assume is more environmentally friendly than feeding them on grain, it’s completely the opposite. It’s the worst possible option. Grazing livestock occupy twice as much land as all the arable and horticultural land put together, yet they provide just over one percent of our diet. It is a fantastically wasteful way of using land.

And in order to keep your livestock on that land, you have to exclude most other wildlife. You have to kill the predators. You have to exclude the competitors, the other herbivores, the wild ones. The livestock wipe out most of the trees because they eat the tree seedlings. The old trees die on their feet and they are not replaced. They wipe out the deep vegetation. They cause a radical simplification of the ecosystem. And as a result of all of that, where livestock are grazed, you end up with more or less a wildlife desert, very low carbon-holding capacity. Lots of damage downstream as well, as soil is eroded, as animal wastes go into the water supply. So doing it with the grazing route is very damaging.

Feeding them on grain is also very damaging. The great majority of the soya plantations which are now devastating South America, wiping out the Gran Chaco dry forests, the Cerrado systems in Brazil, many of the forests around the edges of the Amazon basin—all being destroyed en masse for soya forming. The great majority of that soya goes into animal feed, such that if you want to eat less soya, you should eat soya. The reason being that there’s far more soya embedded in a lump of meat that has been produced in indoor agriculture than there is embedded in a lump of tofu.

Notice how linking phrases automatically highlight the information they link.

What other ways might you highlight something?

Suggestions

pausing before or after a key word, clause or sentence

amplifying an important word, clause or sentence through pitch, volume

Slowing or speeding up the pace to emphasise a point

repeating the same key word to drill it into people's heads

repeating a stem word to clearly join different aspects of a general point (e.g. can + can + can + can, or do + do + do + etc)

using emphatic sentence structures, such as cleft sentences and negative inversions

using emphatic adverbs like "ever" and "yet", also "absolutely", "unbelievably" etc to reinforce extreme adjectives

using deliberate understatement (irony)

using hyperbole (overstatement) and superlative

using emphatic, or extreme, or multiple adjectives (I'm absolutely delirious, thrilled, ecstatic to be part of the team.)

using emphatic punctuation (be careful here!!!)

using short pithy sentences (i.e. "And that was that.")

Using chiasmus (ABBA structures - "It's nice to do it and to do it is nice.")

GEORGE MONBIOT: Well, it is not ____ that meat and dairy production make a huge contribution to climate breakdown. And I call it climate breakdown because calling it climate change is like calling an invading army "unexpected visitors". This is an existential crisis we face. Not just that it also contributes to much wider environmental breakdown, the collapse of biodiversity, the destruction of habitats, the destruction of soil and water resources. But it’s ____ that if we stop eating meat and dairy, we have an enormous potential then for sucking carbon out of the atmosphere. Because so much of the land which is currently occupied by livestock would revegetate if those livestock were removed. Trees could grow back, deep vegetation could grow back and in _____ so, they suck CO2 out of the atmosphere and give us the best possible chance we have of preventing climate chaos and breakdown.

What other ways might you highlight something?

Suggestions

pausing before or after a key word, clause or sentence

amplifying an important word, clause or sentence through pitch, volume

Slowing or speeding up the pace to emphasise a point

repeating the same key word to drill it into people's heads

repeating a stem word to clearly join different aspects of a general point (e.g. can + can + can + can, or do + do + do + etc)

using emphatic sentence structures, such as cleft sentences and negative inversions

using emphatic adverbs like "ever" and "yet", also "absolutely", "unbelievably" etc to reinforce extreme adjectives

using deliberate understatement (irony)

using hyperbole (overstatement) and superlative

using emphatic, or extreme, or multiple adjectives (I'm absolutely delirious, thrilled, ecstatic to be part of the team.)

using emphatic punctuation (be careful here!!!)

using short pithy sentences (i.e. "And that was that.")

Using chiasmus (ABBA structures - "It's nice to do it and to do it is nice.")

Let's review some of the linking structures:

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Can you explain, George, the amount of agricultural land that’s being used to produce food for the livestock—for the livestock and not for human beings—and why you think that’s especially injurious to the climate?

GEORGE MONBIOT: It’s quite remarkable, really. Livestock account for 83 percent of our agricultural land use, according to one study, and produce 18 percent of our diet. It is a huge disproportion. Now ____ you look specifically at grazing livestock, ____ people tend to assume is more environmentally friendly than feeding them on grain, it’s completely the opposite. It’s the worst possible option. Grazing livestock occupy twice as much land as all the arable and horticultural land put together, ___ they provide just over one percent of our diet. It is a fantastically wasteful way of using land.

And ___ order to keep your livestock on that land, you have to exclude most other wildlife. You have to kill the predators. You have to exclude the competitors, the other herbivores, the wild ones. The livestock wipe out most of the trees because they eat the tree seedlings. The old trees die on their feet and they are not replaced. They wipe out the deep vegetation. They cause a radical simplification of the ecosystem. And as a result of all of ____, where livestock are grazed, you end up with more or less a wildlife desert, very low carbon-holding capacity. Lots of damage downstream as well, as soil is eroded, as animal wastes go into the water supply. So doing it with the grazing route is very damaging.

Feeding them on grain is also very damaging. The great majority of the soya plantations which are now devastating South America, wiping out the Gran Chaco dry forests, the Cerrado systems in Brazil, many of the forests around the edges of the Amazon basin—all being destroyed en masse for soya forming. The great majority of that soya goes into animal feed, such ____ if you want to eat less soya, you should eat soya. The _____ being that there’s far more soya embedded in a lump of meat that has been produced in indoor agriculture than there is embedded in a lump of tofu.

Extension cloze

Feeding them on grain is also very damaging. The ____ majority of the soya plantations ____ are now devastating South America, wiping out the Gran Chaco dry forests, the Cerrado systems in Brazil, many of the forests around the edges of the Amazon basin—all being destroyed __ masse for soya forming. The _____ majority of that soya goes into animal feed, such ___ if you want to eat less soya, you should eat soya. The reason ___ that there’s far more soya embedded in a lump of meat that has been produced in indoor agriculture than ____ is embedded in a lump of tofu.

Part 3

From 8:55...

Discuss

What is "free range" meat?

Listen:

From 8:55...

Discuss

What is "free range" meat?

Listen:

1. What does George say about free range meat?

2. What are the three choices we have, according to George?

Gran Chaco deforestation Paraguay

Gran Chaco deforestation Paraguay

Part 4 - a plant based diet

1. What non-vegan foods will George eat?

1. What non-vegan foods will George eat?

2. How have George's tastes changed?

3. What do vegans have to be good at?

4. What does George most want to see happen?

5. How does meat consumption by wealthier societies push up food prices for the poor?

AMY GOODMAN: So let’s talk about your own personal answer and how you changed. You intellectually knew this before, but would you describe yourself as a vegan?

GEORGE MONBIOT: Yes, I’m very close to being a vegan. I will eat venison, deer meat, because in Britain, deer are massively overpopulated because we killed all of the predators. It’s almost impossible to establish new forests because the deer ate all of the seedlings, so we should have fewer deer, we need to cull the deer and I’m happy to eat the wild deer that are culled. I’ll eat roadkill as well, because that has no impact. Apart from that, it is basically one egg a month, which I can’t quite give up eggs altogether, so I’ll eat one egg a month. But apart from that, I don’t eat farmed animal products at all, and I will have a very small amount of wild animal products but that’s it.

AMY GOODMAN: And how hard was it to make that transition for you?

GEORGE MONBIOT: I thought it was going to be really hard. Particularly cheese; I loved cheese. I just thought, “How can I ever possibly give up cheese?” And something very odd happened. Within about a couple of weeks of giving up cheese, suddenly, cheese was just like a lump of lard to me. “Why would I eat this? It’s just—ew, it’s just fat. And it’s weird.” My tastes changed. What I thought I couldn’t do, suddenly, I couldn’t not do. I just don’t like cheese anymore. It’s a very odd thing what happens in the brain, that you adapt to your diet, you adapt to your circumstances and suddenly you like what you are now eating and you don’t like what you were previously eating. So I thought it was going to be really tough, and it wasn’t tough at all.

The one difficult thing about it is you have to be able to cook, if you’re going to have a rich and interesting diet as a vegan. Luckily, in my case, I’m a good cook and I enjoy cooking. But for large numbers of the people to take it up who aren’t into cooking, we do need a wider range of vegan meals. That is happening very rapidly in the U.K. where now seven percent of the population is vegans. That has gone up sevenfold in just three years. It’s a quite remarkable transformation. There’s a massive switch towards veganism here, and the supermarkets and the food manufacturers are responding very quickly to that, making vegan ready meals.

The switch towards plant-based burgers, cultivated meat, cultured meat, making what tastes and looks just like meat out of plant protein, that will massively help as well. And what I really want to see is all of that cheap meat which people eat without thinking, the chicken wings and the pork ribs and whatever else it might be, is quickly and rapidly substituted by cultured meat, which has a far, far lower environmental impact and doesn’t involve cruelty, either.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Despite the fact, as you say, George, that there are increasing numbers of vegans in the U.S., the U.S. remains—reportedly, meat consumption in the U.S. is three times the global average. So could you explain this massive differential? I mean the U.S. and Europe on the one hand, and the rest of the world, poorer countries, where meat consumption is relatively low and small farmers rely on the animals that they raise for their own nourishment? Would you say the same to them?

GEORGE MONBIOT: Well, what we see is an almost linear relationship between income and meat consumption. In the U.K., we eat our body weight in meat every year. In the U.S., you eat one and a half times your body weight in meat every year. And the poorest people eat very little meat. They have pretty well a vegan diet. Now obviously, poor people might want to eat more meat. This is why think the switch towards cheap cultured meat is an environmental priority.

But at present, our massive meat consumption deprives poorer people of their diet because the grains and the pulses which should be grown for human beings are instead grown for livestock, which go into our stomachs. And it’s highly inefficient feeding them to livestock first. You get far more food efficiency out of it if you eat that grain and those pulses directly. At the moment, 50 percent of the plant protein we grow is fed to livestock, rather than to human beings. That pushes up food prices, makes food much more expensive for the poor.

If the rest of the world wanted to switch to our levels of meat eating, well, there simply wouldn’t be enough food to go around. It’s a planetary disaster. There wouldn’t be enough soil. There wouldn’t be enough water. There wouldn’t be enough land. So obviously, that’s not a sensible way to go. What we need to do in the rich nations is to switch toward a plant-based diet. We have the means to do so, we have the technology to do so, we have the choice to do so and I believe that’s the course we should take as quickly as possible.

NB: Monbiot's position on the meat industry has changed several times:

No comments:

Post a Comment